Introduction – Humanity’s Search for Time

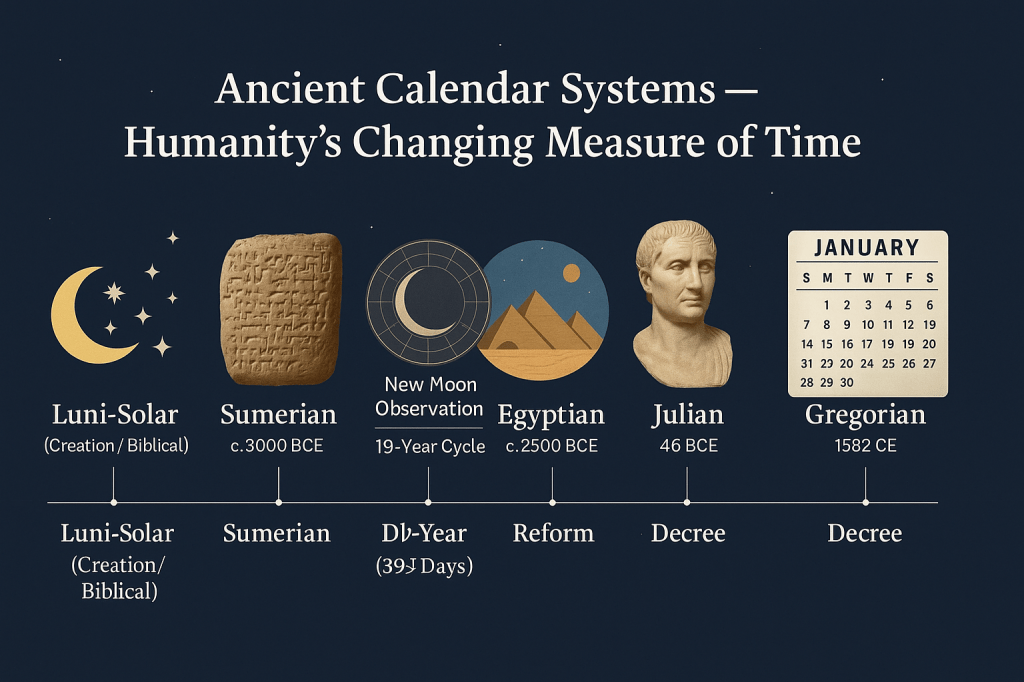

From the dawn of civilization, humanity has sought to measure time. The question has never been whether time exists, but how to reckon it: when does a day begin, when does a month start, how is a year counted? These questions shaped farming, worship, commerce, and empires.

Yet Scripture makes clear that the true measure of time comes from Yahuwah (יהוה):

“Then God (Elohim) said, ‘Let there be lights in the expanse of the heavens to separate the day from the night, and let them be for signs and for appointed times (moedim), and for days and years.’”

— Genesis 1:14

From the very beginning, Yahuwah ordained that the sun, moon, and stars together would be the rulers of time. But as man built cities, kingdoms, and empires, he often replaced Yahuwah’s calendar with his own systems.

This article will explore how various ancient civilizations measured time—Sumerian, Babylonian, Egyptian, and Roman—and then return to the Biblical Calendar to see how it stands apart. Along the way, we will compare lunar, solar, and luni-solar calendars and show how Scripture’s pattern uses all three heavenly lights in harmony.

The Sumerian Calendar – Early Lunar Reckoning

The Sumerians of Mesopotamia (modern-day Iraq) were among the first recorded civilizations to leave behind evidence of a structured calendar. They developed a lunar calendar based on the cycles of the moon, with months beginning at the first visible crescent.

Cuneiform tablets dating back to the third millennium BCE describe how they counted 12 lunar months, each of 29 or 30 days. But because a lunar year is only about 354 days, the Sumerians faced the problem of “drift”—their months slipped earlier and earlier against the solar year. To correct this, they occasionally inserted extra months.

While sophisticated for its time, the Sumerian system was still a human attempt to regulate something Yahuwah had already ordained. Their calendar came after the Biblical pattern set in creation, though it shared one important similarity: it began with the visible new moon.

The Babylonian Calendar – Empire and the 19-Year Cycle

The Babylonians inherited and refined the Sumerian system. By the 6th century BCE, they had developed a full luni-solar calendar:

- Months began with the sighting of the new crescent moon.

- Years were kept in step with the solar cycle through intercalary months.

- They established a 19-year cycle (seven leap months in 19 years) to realign the lunar months with the solar year.

This practice spread widely across the Persian Empire and was even adopted by Greek astronomers (the so-called “Metonic cycle,” though Babylonian records show the idea was already in use centuries earlier).

The Babylonians tied their festivals and temple rituals to this calendar, and later Jewish communities living under Babylonian rule were influenced by it. Month names such as Nisan, Tammuz, and Elul reflect this Babylonian influence—they appear in later biblical and rabbinic texts.

But unlike Yahuwah’s calendar, which is based on direct observation of the heavens and rooted in His appointed times, the Babylonian calendar was primarily an imperial administrative tool. It served to unify taxation, agriculture, and religion across a vast empire.

Still, their use of the new moon as the marker of months provides an important historical witness: even the greatest empires recognized that time could not be divorced from the cycles of the heavens.

External Support:

- The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia confirms that “the months of the year were lunar, and began with the new moon” (UJE, “Calendar,” p. 631).

- Scholar Sacha Stern notes that the Babylonian 19-year cycle was standardized across the Achaemenid empire, showing the attempt to control time politically as well as religiously.

The Egyptian Calendars – Lunar Worship and a Solar Year

While Mesopotamia refined the luni-solar model, ancient Egypt developed a dual calendar system. On one hand, Egypt’s religious festivals often followed a lunar calendar, with months tied to the appearance of the new moon. On the other, the state adopted a civil solar calendar — one of the first purely solar systems in recorded history.

The Egyptian civil year contained 12 months of 30 days, followed by 5 epagomenal days, totaling 365 days. This year was not perfectly aligned with the solar cycle (about 365.2422 days), so over centuries, it drifted against the seasons. To recalibrate, Egyptians observed the heliacal rising of Sirius (Sothis) — a stellar event that roughly coincided with the annual flooding of the Nile. This stellar observation functioned as a celestial “reset,” keeping civil time loosely aligned with the agricultural cycle.

Despite this innovation, lunar reckoning never vanished entirely. Egyptian temple rituals, agricultural festivals, and certain sacred observances still relied on new moon sightings, underscoring how deeply lunar cycles remained woven into timekeeping even in a solar-dominant system.

Historical Support: Egyptologist Richard A. Parker notes that the Egyptians “used three calendars simultaneously: two lunar systems for religious purposes and a civil solar calendar of 365 days,” and that the Sothic cycle played a crucial role in their reckoning of time (The Calendars of Ancient Egypt).

The Roman Calendars – From Chaos to Order

While Mesopotamia and Egypt developed calendars that blended observation and calculation, early Rome’s attempts were far less precise. The pre-Julian Roman calendar was a messy blend of lunar months and political manipulation. It originally had 10 months (March through December), totaling 304 days, with an uncounted winter period. Later, January and February were added, but political leaders routinely added or omitted days and months to lengthen or shorten officials’ terms.

This chaos prompted Julius Caesar to commission a comprehensive reform. In 46 BCE, with the help of Sosigenes of Alexandria, Caesar introduced the Julian calendar — a purely solar calendar of 365.25 days, achieved by adding a leap day every four years. The reform aligned the calendar with the seasons and stabilized civic life.

The Julian system severed the connection between the calendar and the moon. Months no longer began with the new crescent; instead, they became fixed units independent of celestial signs. It was a radical departure from both the Babylonian luni-solar model and the Biblical framework, which linked time to heavenly signs appointed by Yahuwah (Genesis 1:14).

The Gregorian Reform – The Calendar of Empire

Over the centuries, even the Julian calendar drifted. Its average year length of 365.25 days was slightly too long, causing the spring equinox to shift gradually earlier in the calendar year. By the 16th century, this drift had accumulated to about 10 days.

To correct this, Pope Gregory XIII introduced a new reform in 1582 CE, codified in the papal bull Inter gravissimas. Ten days were dropped from the calendar, and a new rule was introduced: century years would only be leap years if divisible by 400. This made the average year length 365.2425 days — much closer to the true solar year.

The Gregorian calendar — the civil standard still used today — is entirely solar-based. It ignores the moon and its cycles completely. Days, months, and years are measured solely by the earth’s orbit around the sun. This calendar’s design reflects not the natural rhythms Yahuwah established, but the needs of political empires and ecclesiastical authority.

Historical Support:

- Encyclopaedia Britannica notes that Julius Caesar’s reform in 46 BCE “replaced the confused lunar calendar with a solar year of 365.25 days” (Julian Calendar).

- It records that Inter gravissimas “dropped 10 days” and revised leap-year rules to correct the drift (Gregorian Calendar).

Comparing Human Systems

By the end of this progression, the calendar humanity follows today has become entirely detached from the signs Yahuwah established. Early calendars — Sumerian, Babylonian, and Egyptian — still looked to the moon and stars for guidance. Rome began by ignoring lunar cycles altogether. The Gregorian system severed the link entirely, using only the sun to measure time.

Each step was driven by human priorities — political stability, imperial administration, or ecclesiastical uniformity. None were built around Yahuwah’s original design.

And yet, throughout all of history, the moon continued to rise, the stars continued to mark the seasons, and the appointed times Yahuwah set in motion at creation (Genesis 1:14) remained unchanged.

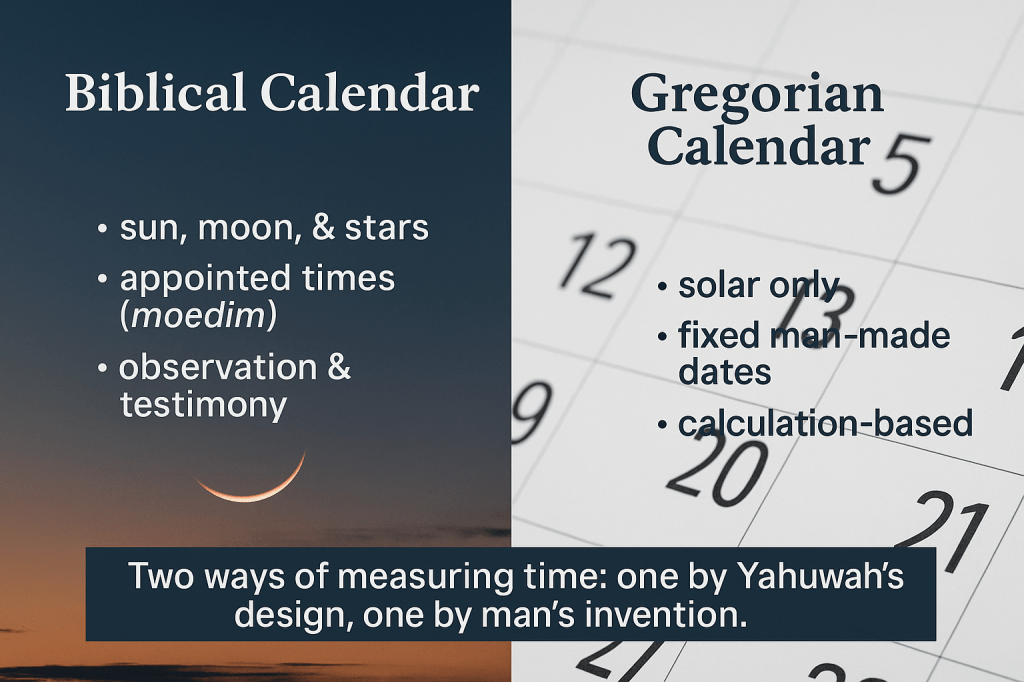

The Biblical Calendar – Yahuwah’s Design

While Sumerian, Babylonian, Egyptian, and Roman systems each shaped the world’s understanding of time, none of them reflected the pattern Yahuwah set in the beginning. His calendar is different. It uses all three lights of heaven together — sun, moon, and stars — to govern days, months, years, and moedim (appointed times).

“Then God (Elohim) said, ‘Let there be lights in the expanse of the heavens… and let them be for signs and for appointed times (moedim), and for days and years.’”

— Genesis 1:14

Psalm 104:19 affirms this: “He appointed the moon for appointed times (moedim); the sun knows its going down.” Here the moon is directly tied to Yahuwah’s sacred appointments, not merely to agricultural seasons.

Throughout Scripture, the new moon (chodesh, חדש) is referenced as the beginning of months:

- Numbers 10:10 — Trumpets blown at new moons and festivals.

- 1 Samuel 20:5, 18, 24 — David and Jonathan acknowledge new moon as a sacred observance.

- Isaiah 66:23 — “From new moon to new moon, and from Sabbath to Sabbath…”

- Ezekiel 46:1–3 — The sanctuary gates opened specifically for Sabbaths and new moons.

This is not a minor theme. The new moon day was distinct from both ordinary work days and Sabbaths. It functioned as a reset point for each month, aligning with Yahuwah’s creation order.

Declaring the Month – Witness and Observation

How was the new month established in practice? Scripture points to the new moon as the marker, and historical records confirm this was done by eyewitness testimony.

- Mishnah Rosh Hashanah 2 records that witnesses would testify before the Sanhedrin that they had seen the crescent.

- Arthur Spier, in The Comprehensive Hebrew Calendar (p.1), writes: “The beginning of the months were determined by direct observation of the new moon. Then those beginnings of months (Rosh Chodesh) were sanctified and announced by the Sanhedrin, the Supreme Court in Jerusalem, after witnesses testified that they had seen the new crescent and after their testimony had been thoroughly examined.”

The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia explains the process:

“On the thirtieth day of the month a council would meet to receive the testimony of witnesses that they had seen the new moon. If two trustworthy witnesses had made deposition… the council proclaimed a new month to begin on that day. If no witnesses appeared, the new moon was considered as beginning on the day following the thirtieth.” (UJE, p.632)

This confirms that in the time of Yahshua (Jesus), no fixed calculated calendar yet existed. Emil Schürer, in The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ, writes:

“They did not in the time of Jesus Christ possess as yet any fixed calendar, but on the basis of a purely empirical observation, on each occasion they began a new month with the appearing of the new moon…” (Schürer, p.366).

The New Moon as a Sacred Festival

The new moon was not only a marker of time but also a day of worship. Philo of Alexandria (1st century CE), a Jewish philosopher contemporary with Yahshua, describes it as a sacred occasion:

- Philo, Special Laws II, 141: “At the time of the new moon, the sun begins to illuminate the moon with a light visible to the outward senses, and then she displays her own beauty to the beholders.”

- Philo, Book 26, XXX, 159: “The sacred festival of the new moon, which the people give notice of with the trumpets, and the day of fasting, on which abstinence from all meats and drinks is enjoyed…”

These testimonies show that the new moon was a living practice in the Second Temple period, recognised as both a sacred marker of time and a festival day.

From Observation to Calculation – Hillel II’s Reform

The original system of observing the new crescent continued until the 4th century CE. Then, Roman persecution made it impossible for the Sanhedrin to convene. In response, Hillel II (c. 359 CE) instituted a calculated calendar, fixing the dates of months and festivals by mathematical rule rather than direct observation.

As torah.org summarizes:

“Declaring the new month by observation of the new moon… can only be done by the Sanhedrin. In the time of Hillel II, the Romans prohibited this practice. Hillel II was therefore forced to institute his fixed calendar…”

This marked a turning point: what Yahuwah established in creation as an observed sign in the heavens was now reduced to calculation on paper.

Week and Month Connections

Some historical sources suggest that in the most ancient times, the week itself was tied to the lunar cycle. The Universal Jewish Encyclopedia (Vol. 10, p.482, “Week”) notes:

“Each lunar month was divided into four parts, corresponding to the four phases of the moon. The first week of each month began with the new moon…”

The Encyclopedia Biblica (1899, pp.4178–4179) observes that in older Hebrew texts, the new moon and Sabbath are almost invariably mentioned together, showing an early connection between the two. Over time, this connection weakened, and the week developed independently of lunar phases.

Whether or not the Sabbath was originally lunar-phased, these records highlight how deeply lunar reckoning once shaped sacred time.

Why This Matters – Appointed Times and the Return of Yahshua

Understanding how humanity has measured time is more than an exercise in history — it shapes how we understand Yahuwah’s appointed times (moedim) and prepares us for the return of Yahshua (Jesus). Scripture tells us these appointed times were established “forever throughout your generations” (Leviticus 23:14, 21, 31, 41), and they remain central to Yahuwah’s redemptive plan.

Yet on the Gregorian calendar — the one nearly all of humanity follows — these appointed times are invisible. The Gregorian system:

- Begins its days at midnight, not dawn or sunset.

- Begins its months on arbitrary dates, not the new moon.

- Marks its years without reference to the equinox or signs in the heavens.

As a result, the appointed times Yahuwah set — Passover (Pesach), Unleavened Bread, First Fruits, Pentecost (Shavuot), Trumpets (Yom Teruah), Atonement (Yom Kippur), and Tabernacles (Sukkot) — cannot be accurately identified on the Gregorian calendar. It is not just a different system; it is an entirely different way of reckoning time.

Scripture warns that at Yahshua’s return, there will be only 144,000 who “keep the commandments of God and the faith of Yahshua” (Revelation 14:12), yet there will also be a “great multitude which no man could number” (Revelation 7:9). Many scholars believe this reflects a distinction between those who have fully aligned their lives with Yahuwah’s ways — including His times — and those who respond to Him in the last days but did not walk in His calendar beforehand.

A Tale of Two Calendars

| Feature | Biblical Calendar | Gregorian Calendar |

|---|---|---|

| Basis of time | Sun, moon, and stars (Genesis 1:14) | Solar only |

| Start of month | First visible crescent (Numbers 10:10) | Arbitrary (1st of month) |

| Start of day | Dawn or sunset (debated) | Midnight |

| Appointed times | Fixed by lunar-solar signs | Cannot be accurately plotted |

| Origin | Divine appointment | Human invention (46 BCE / 1582 CE) |

This comparison highlights why Yahuwah’s moedim cannot simply be “translated” into the Gregorian system. They are not meant to conform to man-made constructs; they are written in the heavens.

The Path Forward – Returning to the Ancient Ways

“Thus says Yahuwah: ‘Stand in the ways and see, and ask for the old paths, where the good way is, and walk in it; then you will find rest for your souls.’”

— Jeremiah 6:16

The “old paths” are not merely ancient customs — they are Yahuwah’s ordained ways. They include His Sabbath (Shabbat), His moedim, and His way of measuring time. These are not burdens but blessings — opportunities to walk in step with the Creator’s design.

Rediscovering the Biblical Calendar is not about rejecting all human systems, but about recognising that Yahuwah’s time is higher, older, and unchanging. When we align with His appointed times, we step into a rhythm that has existed since creation and will continue into eternity (Isaiah 66:23).

Conclusion – Time and the Kingdom

From the moon-watchers of Sumer to the mathematicians of Babylon, from Egypt’s solar priests to Caesar’s astronomers, humanity has sought to master time. The Gregorian calendar — now the global standard — is the culmination of those efforts. But in the process, mankind has moved further from the pattern Yahuwah set in motion “in the beginning.”

His calendar remains unchanged. It still begins with the new moon, still marks the appointed times, and still invites His people to meet with Him at the times He appointed. As Yahshua’s return draws near, understanding and walking in this divine rhythm becomes more than historical curiosity — it becomes a call to readiness.

The question is not whether Yahuwah’s calendar still matters — it is whether we are willing to set aside man’s timekeeping and step back into His.

References

Scripture

Genesis 1:14; Psalm 104:19; Numbers 10:10; 1 Samuel 20:5, 18, 24; Isaiah 66:23; Ezekiel 46:1–3; Leviticus 23:4, 14, 21, 31, 41; Revelation 7:9; Revelation 14:12; Jeremiah 6:16; Colossians 2:16–17.

Primary & Historical Sources

- Philo, Special Laws II, §141; Book 26, XXX, §159.

- Mishnah Rosh Hashanah 2; Talmud Rosh Hashanah 22 – New moon witnesses.

- Arthur Spier, The Comprehensive Hebrew Calendar, p.1.

- Universal Jewish Encyclopedia – “Calendar,” pp. 631–632; “Week,” Vol. 10, p. 482; “Holidays,” p. 410.

- Encyclopedia Biblica (1899), pp. 4178–4179, 5290.

- Emil Schürer, The History of the Jewish People in the Age of Jesus Christ, p. 366.

- George Foot Moore, Judaism, Vol. 2, p. 22.

- torah.org, “The Jewish Calendar: Changing the Calendar.”

Scholarly Works on Ancient Calendars

- Sacha Stern, Rabbinic, Christian, and Local Calendars in Late Antique Babylonia.

- Richard A. Parker, The Calendars of Ancient Egypt.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica, “Julian Calendar,” “Gregorian Calendar.”