Author’s Note: This article is the first in a 10-part series exploring Yahuwah’s (יהוה) original calendar, His appointed times, and the return of Yahshua (ישוע). This series aims to help believers understand the biblical way of measuring time and how it differs from the modern calendar we use today.

Introduction – Why Time Matters in Understanding Yahuwah’s Plan

Time is one of the most fundamental parts of life, yet it is also one of the most misunderstood. From the moment we are born, time governs everything: when we eat, when we sleep, when we work, and when we rest. It defines our celebrations, our seasons, and even our faith traditions. We accept this system as absolute — rarely stopping to ask if the way we measure time is the same way Yahuwah (יהוה) designed it to be measured.

But what if the calendar we use today — the one we inherited without question — is not the one the Creator set in place? What if by using a man-made calendar, we have drifted away from the rhythm Yahuwah intended for His people? And what if understanding that original calendar is a key to unlocking deeper truths about His appointed times and the return of Yahshua (ישוע)?

This series will walk step by step through that very question. We will examine how humanity has measured time across history, how Scripture reveals a different calendar altogether, and how rediscovering that original design sheds new light on prophecy, worship, and the days to come.

The Names Above All Names – יהוה (Yahuwah) and ישוע (Yahshua)

Before we begin, it is important to address the names we will use throughout this series. In most English Bibles, the name of the Creator is translated simply as “the LORD”, or as “God”. Yet the Hebrew text gives us His personal name: יהוה (Yahuwah). Likewise, the Messiah is widely known today as “Jesus,” but His Hebrew name is ישוע (Yahshua), meaning “Yahuwah saves.”

Using these original names reconnects us to the Hebraic roots of Scripture and reminds us that this journey is about returning to what was established “in the beginning.” These names are not new — they are ancient and sacred, and they appear throughout Scripture. As Yahuwah declares:

“… This is My name forever, and this is My memorial unto all generations.”

— Exodus 3:15

How We Learn Time as Children

From our earliest years, we are taught how to measure time. We learn that a day begins at midnight and ends at 11:59 PM. We memorise that there are seven days in a week, that months have 30 or 31 days (and one has 28, except every four years), and that a year always begins on January 1. We learn the names of the months and days of the week as unchangeable facts — so ingrained that we never think to question them.

Teachers, parents, books, and even children’s songs reinforce this structure. “Thirty days hath September…” — and so it is. Because we are introduced to these ideas so young, they become part of our worldview. We grow up believing this is the natural way of things, the way it has always been.

The problem is that none of this is inherently divine. It is a man-made system that we inherit and internalise without question. And once we have accepted it, anything that differs from it feels foreign, strange, or even “wrong.”

Scripture warns us of this very danger:

“There is a way that seems right to a man, but its end is the way of death.”

— Proverbs 14:12

The fact that something “seems right” does not mean it is right — and this is especially true when it comes to time. The way we understand and measure time shapes how we understand Scripture, how we worship, and how we anticipate Yahuwah’s appointed times. If our foundation is flawed, everything built upon it will be misaligned.

The Gregorian Calendar: A Man-Made System

The calendar almost the entire world uses today is called the Gregorian calendar. It was introduced in 1582 CE by Pope Gregory XIII as a reform of the older Julian calendar, which itself was introduced by Julius Caesar in 46 BCE. The Julian calendar had slowly drifted out of alignment with the solar year because it miscalculated the length of the year by about 11 minutes. That error added up over centuries, causing the dates of seasonal events — including church holidays like Easter — to shift.

The Gregorian reform corrected this drift by shortening the average year and adjusting leap year rules. Most Catholic countries adopted it quickly, while Protestant nations resisted for more than a century before eventually following suit. By the 20th century, nearly the entire world had embraced it.

The result is a solar-only calendar — one based entirely on Earth’s orbit around the sun. Its months are named for Roman gods and emperors:

- January – named after Janus, the Roman god of beginnings

- March – named after Mars, the god of war

- July – named after Julius Caesar

- August – named after Emperor Augustus

It is worth pausing here to recognise what this means: the calendar we trust without question is both man-made and deeply rooted in pagan Roman culture. It is not the calendar described in Scripture, nor is it the system Yahuwah ordained for His people.

“He shall speak pompous words against the Most High, shall persecute the saints of the Most High, and shall intend to change times and law.”

— Daniel 7:25

This prophecy is sobering. It shows that the manipulation of time — the very structure by which people order their lives — was foreseen as part of the rebellion against Yahuwah. The adoption of a man-made calendar in place of Yahuwah’s is not a trivial matter. It affects when we worship, when we rest, and how we interpret prophecy.

Why We Resist Other Ways of Measuring Time

Because we have known only one calendar our entire lives, we instinctively resist anything that challenges it. When we encounter talk of lunar months, new moon days, or biblical appointed times, it sounds strange — even suspicious. This is not because these ideas are false, but because they do not fit the mental framework built into us since childhood.

Our minds are wired to cling to what is familiar. Psychologists call this “confirmation bias” — the tendency to interpret new information in ways that confirm what we already believe. It is the same principle Yahshua spoke of when He said:

“No one puts new wine into old wineskins; or else the new wine will burst the wineskins and be spilled, and the wineskins will be ruined. But new wine must be put into new wineskins, and both are preserved.”

— Luke 5:37-38

If we are to understand Yahuwah’s calendar, we must become like new wineskins — willing to unlearn and relearn. Yahuwah reminds us:

“For My thoughts are not your thoughts, nor are your ways My ways,” says Yahuwah. “For as the heavens are higher than the earth, so are My ways higher than your ways, and My thoughts than your thoughts.”

— Isaiah 55:8-9

This is not just a theological point — it is a practical reality. If our concept of time is shaped by a man-made calendar that Yahuwah never commanded, then our understanding of His appointed times will also be shaped — and limited — by that same framework.

A Glimpse of Yahuwah’s Time in Scripture

If the Gregorian calendar is man-made, what does Yahuwah’s system look like? Scripture gives us the answer right from the beginning:

“Then Elohim said, ‘Let there be lights in the firmament of the heavens to divide the day from the night; and let them be for signs and for seasons and for days and years.’”

— Genesis 1:14

The Hebrew word translated “seasons” here is moedim (מועדים), which does not refer to spring, summer, autumn, or winter. It means appointed times — the sacred days and festivals Yahuwah set apart for His people. This verse shows that the sun, moon, and stars were created not just to mark time, but to reveal His appointed times.

This principle is repeated elsewhere:

“He created the moon for seasons; the sun knows its going down.”

— Psalm 104:19

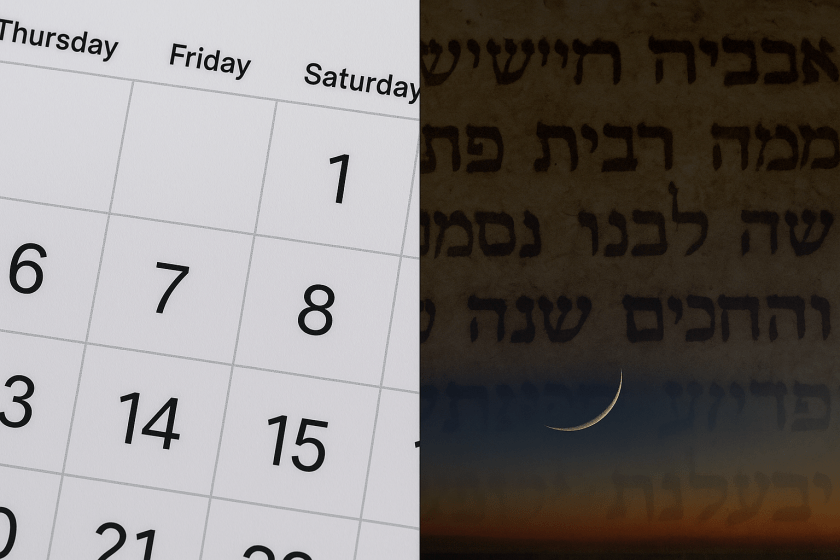

The moon is central to Yahuwah’s calendar. It is not just a light in the night sky — it sets the rhythm of months and appointed times. The Hebrew word for “month” is chodesh (חדש), meaning new moon. Each biblical month begins with the visible appearance of the new moon. This is why the biblical calendar is often called lunar-solar — it uses the sun to mark days and years, and the moon to mark months and appointed times.

Yahuwah also commanded that the new month be recognised with trumpet blasts and offerings:

“Also in the day of your gladness, in your appointed feasts, and at the beginnings of your months, you shall blow the trumpets over your burnt offerings and over the sacrifices of your peace offerings; and they shall be a memorial for you before your Elohim: I am Yahuwah your Elohim.”

— Numbers 10:10

The beginning of each month — marked by the new moon — was not just a date; it was a sacred moment. It reset the cycle of time and prepared the way for the appointed times to come and is a major difference between the calendar in use today and the one we find in the Scriptures.

Moedim and Chodesh: Understanding the Biblical Rhythm

The biblical calendar is built on two key concepts:

- Moedim (מועדים) – Appointed times, set by Yahuwah, tied to specific days and months. These include Passover, Unleavened Bread, First Fruits, Pentecost, Trumpets, Day of Atonement, and Feast of Booths.

- Chodesh (חדש) – New moon, marking the beginning of each month and resetting the count toward the moedim.

This system is completely different from the Gregorian calendar, which uses fixed solar months that ignore the moon entirely. In Yahuwah’s system, the moon acts much like the modern International Date Line — it resets the count of days and keeps His people aligned with His timing.

The significance of this is profound. It means that time in Scripture is not an abstract concept — it is an ongoing covenant marker between Yahuwah and His people. It shapes the rhythm of worship, the cycle of festivals, and even the prophetic timeline.

“These are the appointed feasts of Yahuwah, holy convocations which you shall proclaim at their appointed times.”

— Leviticus 23:4

This chapter goes on to list the moedim — Yahuwah’s appointed times — each anchored to a specific day of a specific month, counted from the new moon.

Conclusion – Time to Relearn Time

We began this journey by questioning something most people never think to question: time itself. We saw how the calendar we trust was created by men and steeped in pagan history. We saw how deeply ingrained it is in our thinking — and how that very familiarity can blind us to Yahuwah’s original design.

But we also glimpsed something deeper: a biblical system rooted not in tradition, but in creation itself — the sun, moon, and stars working together to reveal Yahuwah’s moedim. These appointed times are not merely ancient rituals. They are prophetic markers, unfolding Yahuwah’s plan of redemption through Yahshua and pointing us toward His return.

The world measures time one way. Yahuwah measures it another. And if we want to walk in step with Him, it is time to relearn how we understand time itself.

“Thus says Yahuwah: ‘Stand in the ways and see, and ask for the old paths, where the good way is, and walk in it; then you will find rest for your souls.’”

— Jeremiah 6:16

The Path Ahead: Roadmap of the Series

This article is just the beginning of a much larger journey. Over the coming weeks, we will walk through a 10-part series that reveals how Yahuwah’s calendar unveils His plan of redemption and points directly to the return of Yahshua (ישוע):

- How We Learned Time — And Why It’s Time to Relearn It (this article)

- Ancient Calendar Systems – How humanity has measured time across the ages.

- Modern Timekeeping and Its Variations – Why the Gregorian calendar isn’t universal.

- Yahuwah’s Biblical Calendar – How the Bible instructs us to measure time.

- God’s Appointed Times (Moedim) – The prophetic meaning of each feast.

- Why the Gregorian Calendar Hides These Appointments – Understanding the disconnect.

- The 144,000 and the Great Multitude – Why obedience and timing matter.

- The Day of Trumpets and Prophecy – How this feast connects to Yahshua’s return.

- When Time Changed: From 360 Days to the Divided Years – and Its Coming Restoration

- The Appointed Harvest – Barley, Wheat, and the 1,335-Day Prophetic Countdown

Each step will bring us closer to understanding Yahuwah’s appointed times — not as relics of the past, but as living signposts pointing toward the future.

What’s Next

In the next article, “Ancient Calendar Systems,” we will explore how humanity measured time before the Gregorian calendar — from lunar observations in Mesopotamia and Egypt to the Hebrew calendar described in Scripture. By understanding these ancient systems, we will see even more clearly how Yahuwah’s design stands apart.

References

Scriptural References

- Genesis 1:14 – The sun, moon, and stars appointed for signs, seasons (moedim), days, and years.

- Psalm 104:19 – Yahuwah appointed the moon for moedim.

- Numbers 10:10 – Trumpets to be blown at the beginning of months (chodesh) and appointed feasts.

- Leviticus 23:4 – The appointed times (moedim) of Yahuwah proclaimed at their set times.

- Daniel 7:25 – Prophecy of one intending to change “times and laws.”

- Isaiah 55:8–9 – Yahuwah’s thoughts and ways are higher than ours.

- Luke 5:37–38 – The parable of new wine and old wineskins.

- Proverbs 14:12 – “There is a way that seems right to a man…”

- Jeremiah 6:16 – “Ask for the old paths…”

- Exodus 3:15 – Yahuwah’s name to be remembered for all generations.

Historical and Scholarly References

- Richards, E. G. Mapping Time: The Calendar and Its History. Oxford University Press, 1998.

- Blackburn, B. & Holford-Strevens, L. The Oxford Companion to the Year. Oxford University Press, 1999.

- Stern, Sacha. Calendar and Community: A History of the Jewish Calendar, Second Century BCE–Tenth Century CE. Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Beckow, G. The Hebrew Calendar: A Guide to the Biblical Moedim. Jerusalem Press, 2015.

- Hannah, Robert. Greek and Roman Calendars: Constructions of Time in the Classical World. Duckworth, 2005.

- Humphreys, Colin J. “The Jewish Calendar, A Lunar Eclipse, and the Date of Christ’s Crucifixion.” Tyndale Bulletin 43.2 (1992): 331–351.

- Council of Trent (1545–1563) – Historical records of the Gregorian calendar reform under Pope Gregory XIII.

- International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service (IERS). Bulletin C – Leap seconds and modern timekeeping.

Shalom🙏You need to learn how to spell YAHUAH. The letter W was only invented

LikeLike

Shalom, and thank you for your comment. It’s important to understand that none of the English letters we use today existed in the original language — they are simply symbols used to represent sounds. What matters is the sound being conveyed, not the specific character chosen to represent it. Different regions and languages may use different letters to express the same sound, but the underlying pronunciation remains the same.

The original spelling of the Name in Hebrew is: יהוה — this is the form found in the ancient texts. The English rendering “Yahuwah” is simply an attempt to represent the same sounds in our alphabet.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Shalom 🙏There were no w sounds

LikeLike

Shalom, and thank you for sharing your perspective. It’s worth remembering that our modern alphabet — including the letters “W” and “V” — did not exist at all in the ancient world.

These are later symbols created to represent certain sounds, and different regions and languages have always represented those sounds in different ways.

For example, in German and several Eastern European languages, what English speakers write as a “W” is pronounced with a “V” sound. In Dutch and Afrikaans, “W” is often a soft “V,” and in many South Asian languages there is no distinction between the two at all. This shows us that the sound is far more significant than the symbol used to write it.

The original Hebrew name is יהוה — and regardless of whether we attempt to represent it as “Yahuah,” “Yahuwah,” or another transliteration, the aim is always to express the same sacred sounds as closely as possible within the limits of our language.

LikeLike

What is the new moon? Is it what we were taught to call it the full moon?

LikeLike

Dear Jane,

Thank you for your question — it’s an important one, and one that has been misunderstood by many over time. The short answer is: the new moon is not the full moon. The new moon is the beginning of the month and marks the first visible crescent of the moon after it has been dark.

Some people point to Psalm 81:3 to argue that the new moon is the full moon. However, that verse, when read carefully in Hebrew, mentions three separate things: the new moon (chodesh), the full moon (kece), and the feast (chag). It does not say the new moon is the full moon. Instead, it shows they are distinct events.

We know from Numbers 33:3 that Israel left Egypt on the 15th day of the first month, which was a full moon — and from Leviticus 23:5–6, that was also the first day of the Feast of Unleavened Bread. Since the 15th day is the full moon, the 1st day — the new moon day — must come before it, marking the start of the month.

We see this clearly in 1 Samuel 20:24–27, where the new moon is called the first day of the month, and the next day is the second day. The full moon happens about two weeks later.

History and ancient sources confirm this. The ancient Hebrews determined the start of the month not by calculation but by observation — specifically, when the first thin crescent of the moon became visible just after sunset. Witnesses would report its appearance, and the Sanhedrin in Jerusalem would proclaim the new month had begun. This was the practice described in the Mishnah, Talmud, and by writers like Philo of Alexandria in the first century.

The Hebrew word for new moon, chodesh, comes from chadash, meaning “to renew” or “repair.” This renewal begins when the first sliver of light becomes visible. That is the new moon — the start of the lunar month — and from that point, the moon grows (waxes) to full brightness around the 15th day, then wanes back to darkness before renewing again.

In short, the new moon marks the beginning of the month with the first visible crescent, not the full moon. The full moon, by contrast, marks the middle of the month, around day 15, and is often associated with major feast days like Unleavened Bread and Tabernacles.

I hope this clears up the confusion and gives you a deeper understanding of how the new moon is defined both in Scripture and in historical practice.

Kind regards,

Robert-Aaron

LikeLike